The body of Saartjie Baartman, better known as the Hottentot Venus, has had a greater influence on the iconography of the female body in European art and visual culture than any other African woman of the colonial era. Saartjie, a South African showgirl in the early 19th century, was a small, beautiful woman, with an irresistible bottom. Of a build unremarkable in an African context, to some western European eyes, she was extraordinary. Today, she is celebrated as bootylicious.

Saartjie was not only the African woman most frequently represented in racially marked British and French visual culture, but she also had less immediately visible influences on western art. In an age when art and science were commonly regarded as bedfellows, her image appeared in a proliferation of media, from popular to high culture. Saartjie was depicted in scientific and anatomical drawings, in playbills and aquatint posters, in cartoons, paintings and sculpture. Both during her life and after her death, caricaturists Thomas Rowlandson and George Cruikshank made her the subject of works typifying London life and the Napoleonic era. Saartjie’s body cast was one of the inspirations for Matisse’s revolutionary restructuring of the female body in The Blue Nude (1907), prompted by African sculpture and conceived, as Hugh Honour argues, “as an ‘African’ Venus: that her skin is not black is hardly of significance in view of his attitude to colour”.

Who was Saartjie Baartman? Not a question anyone will ask in South Africa, where she is a national icon; nor in America, where her life, legend and relevance are well understood. Yet in Britain, where she came to fame and had such an influence, she is less well remembered. Rumoured to be a slave brought to England against her will, Saartjie was an orphaned Khoisan maidservant born in 1789 on the eastern frontier of the Cape Colony. She was 21 years old when she was smuggled from Cape Town to London. Her employer, a free black man named Hendrik Cesars, was manservant to a British Army medical officer named Alexander Dunlop. Dunlop persuaded Cesars that Saartjie had lucrative potential as entertainment and a scientific curiosity in England, which had a thriving stage trade in human and scientific curiosities. A woman from the so-called “Hottentot tribe”, who, legend held, had amazing buttocks and strangely elongated labia, might provide an exceptional draw. Saartjie was persuaded: Dunlop, she said, had “promised to send her back rich”.

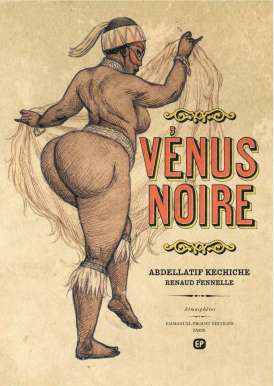

Billed as the Hottentot Venus, Saartjie first performed in Piccadilly on September 24 1810. Dre ssed in a figure-hugging body stocking, beadwork, feathers and face-paint, she danced, sang and played African and European folk songs on her ramkie, forerunner to the tin-can guitar. Slung over her costume was a voluminous fur cloak (kaross). Enveloping her from neck to feet, it was an African version of the corn-gold tresses of Botticelli’s Venus – and every inch of its luxuriant, curled hair was equally suggestive.

ssed in a figure-hugging body stocking, beadwork, feathers and face-paint, she danced, sang and played African and European folk songs on her ramkie, forerunner to the tin-can guitar. Slung over her costume was a voluminous fur cloak (kaross). Enveloping her from neck to feet, it was an African version of the corn-gold tresses of Botticelli’s Venus – and every inch of its luxuriant, curled hair was equally suggestive.

To London audiences, she was a fantasy made flesh, uniting the imaginary force of two powerful myths: Hottentot and Venus. The latter invoked a cultural tradition of lust and love; the former signified all that was strange, disturbing and – possibly – sexually deviant. Almost overnight, London was overtaken by Saartjie mania. Within a week, she went from being an anonymous immigrant to one of the city’s most talked-about celebrities. Her image became ubiquitous: it was reproduced on bright posters and penny prints, and she became the favoured subject of caricaturists and cartoonists.

Bottoms were big in late-Georgian England. From low to high culture, Britain was a nation obsessed by buttocks, bums, arses, posteriors, rumps – and with every metaphor, joke or pun that could be squeezed from this fundamental distraction. Georgian England both celebrated and deplored excess, grossness, bawdiness and the uncontain able. In Rowlandson’s cartoon, amply proportioned white Englishwomen are depicted trying to plump up their already big bottoms in imitation of Saartjie, who loftily presides over them all.

able. In Rowlandson’s cartoon, amply proportioned white Englishwomen are depicted trying to plump up their already big bottoms in imitation of Saartjie, who loftily presides over them all.

Saartjie’s instant celebrity owed much to a coincidence between the Georgian fascination with bottoms, the size of the derrière of Lord Grenville, and the British tradition of visual satire. The aristocratic Grenville family were famed for their huge bums. The nation was rife with speculation that Grenville would become prime minister and his Whig coalition – known as the broad-bottoms or the bottomites – take over parliament. An engraving by William Heath depicts Grenville dressed as the Hottentot Venus. In another, by George Cruikshank from 1816, Saartjie’s profile is compared with that of the Prince Regent.

A month after Saartjie’s show opened, the abolitionists, convinced she was brought to England and forced to perform against her will, began a High Court lawsuit on her behalf that electrified the English public and press. When asked whether she would prefer to go to Bible school and then return home, or stay in England performing with a contract and a salary, Saartjie said, “Stay here.” Unable to prove that she performed unwillingly, the case collapsed. Her choices were limited: a return to servitude in colonised South Africa, or exploitation in free England. The Hottentot Venus show went on.

Saartjie arrived in France in 1814, a recognised icon preceded by her reputation as a scantily clad totem goddess. Napoleonic Paris greeted her as a celebrity. In France, as in Britain, her image proliferated – with a significant difference: where English representations exaggerated the size of her buttocks, French portrayals show attempts to be more true to life.

In the spring of 1815, Saartjie posed for three days as a life model for a panel of Europe’s leading Enlightenment scientists, naturalists, and staff painters at the Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle. Georges Cuvier, Henri de Blainville and Étienne Saint-Hilaire led the scientific team. Resident artists Léon de Wailly, Nicolas Huet and Jean-Baptiste Berré produced delicate watercolour portraits of her figure. As well as integral to the “scientific” project, these illustrations became collectible popular art, copied and sold in great quantity. De Wailly’s tactful portrait – used as her official image by the ANC – is drawn with evocative, poignant sensibility. In this image Saartjie stands in the antique pose of the Cnidian Venus, so beloved of Renaissance sculptors; a figure that would reappear later in the 19th century in the Orientalist grandes odalisques of Ingres and Renoir.

Saartjie died at the end of 1815, aged just 26. Indignity followed her in death: within 48 hours, her body had been dissected, her bones boiled, and her brain and genitals bottled. Cuvier, the father of both comparative anatomy and palaeontology, conducted the post-mortem examination. Plaster casts were taken of her body. Once the whole figure was integrated, “sculptors and artists finished the lines to the mould, polished the model surface with oil of turpentine, and then skin, vessels were painted on; the whole covered in a coat of clear varnish”. For nearly two centuries these relics were kept in the Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, on public display. Posthumously imprisoned in Paris, Saartjie’s violated body became one of Europe’s most analysed specimens. From these lifeless and fragile remnants, European scientists manufactured monstrous, crackpot pseudo-scientific theories proposing biological differences between human groups.

South Africa never forgot Saartjie. The end of apartheid was the crucial turning point in her afterlife. In 1994, when the African National Congress achieved the country’s transition to non-racial democracy, President Mandela raised the matter of Saartjie with President Mitterrand during his first state visit to South Africa. Supporting the long-running campaign for the return of Saartjie’s remains initiated by the anthropologist Professor Philip Tobias, Mandela told Mitterrand that it was time for her to come home.

South Africa never forgot Saartjie. The end of apartheid was the crucial turning point in her afterlife. In 1994, when the African National Congress achieved the country’s transition to non-racial democracy, President Mandela raised the matter of Saartjie with President Mitterrand during his first state visit to South Africa. Supporting the long-running campaign for the return of Saartjie’s remains initiated by the anthropologist Professor Philip Tobias, Mandela told Mitterrand that it was time for her to come home.

Claiming right of possession to Saartjie’s remains and honouring her as a heroic national ancestor was the first act of international cultural reparation made on behalf of free South Africa. The French people and politicians supported her repatriation, but museologists raised ridiculous objections that she was still a viable object of “scientific” study and French patrimony. Henri de Lumley, director of the Musée de l’Homme, claimed insultingly that she would be “safer” and better preserved “cherished in the home of liberty, fraternity and equality, than in South Africa”.

Saartjie’s remains became central to the ongoing debate over the return of the cultural heritage, plundered from formerly colonised nations, that fills European museums. Responding to the hysteria that Saartjie’s return would open the floodgates to similar requests, Ben Ngubane, minister of culture, wryly observed that South Africa was unlikely to request the return of all its plundered patrimony, as there isn’t room in Africa to store it. Brigitte Mabandla, deputy minister of culture, pointed out that: “The end of colonialism is tied to the return of Africa’s cultural heritage … Scholars argue that 200-year-old remains should be classified as ordinary artifacts, and tools for research, and that there is no need to attach emotions to them. This is a fallacy. Europe is littered with ancient heritage, and there is a lot of passion associated with heritage by Europeans themselves.” It took a further eight years and the intervention of Mandela’s successor, Thabo Mbeki, before Saartjie’s remains were released. In May 2002 they were flown back to South Africa, and on August 9, National Women’s Day, Saartjie was honoured with a state funeral in the Gamtoos River Valley, her birthplace. Mbeki gave her funeral speech. Today, Saartjie Baartman is modern South Africa’s most revered female historical icon of the colonial era.

It took a further eight years and the intervention of Mandela’s successor, Thabo Mbeki, before Saartjie’s remains were released. In May 2002 they were flown back to South Africa, and on August 9, National Women’s Day, Saartjie was honoured with a state funeral in the Gamtoos River Valley, her birthplace. Mbeki gave her funeral speech. Today, Saartjie Baartman is modern South Africa’s most revered female historical icon of the colonial era.

Saartjie’s legacy has been to carry the burden of racist representation for colonial and imperialist history. Visual representations of her body are fraught with the negative consequences of reproducing offensive iconography. These images persist as products of a white society whose imposed perceptions damaged and subordinated the lives, consciousness and body-image of millions of people. The history of the Hottentot Venus raises vexing questions about intention and audience when reproducing racist representations, but it also highlights the dangers of censorship. Images of Saartjie are part of her story: they will offend, but no good ever came of locking pictures in the attic. Images of subjected slaves kneeling, or celebrating their release, were unthinkingly reproduced long after abolition.

It’s striking that Saartjie was never shown in a classic slave image. This is not to propose some fatuous notion of a more liberal intention by the white men who depicted her: these men, and their racialised perceptions, were products of their time. Saartjie’s body was subjected to indignity and exaggeration, but there has been less careful reflection on the ways in which she subsequently influenced the emergence of the modernist female form, or of how she might be celebrated now, as she is in African and transatlantic black popular music and body culture. Hopefully, a new exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery, timed to coincide with the 200th anniversary of the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act, will begin to challenge the omission of Saartjie and recognise her influence on British culture.

This is not to propose some fatuous notion of a more liberal intention by the white men who depicted her: these men, and their racialised perceptions, were products of their time. Saartjie’s body was subjected to indignity and exaggeration, but there has been less careful reflection on the ways in which she subsequently influenced the emergence of the modernist female form, or of how she might be celebrated now, as she is in African and transatlantic black popular music and body culture. Hopefully, a new exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery, timed to coincide with the 200th anniversary of the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act, will begin to challenge the omission of Saartjie and recognise her influence on British culture.

Far from outlandish or unfamiliar to the western eye, the evolving historical conventions of the female nude in European art are apparent in many representations of the Hottentot Venus, as is her influence. Saartjie’s death in Paris coincided with the repatriation to Italy of the famous Roman statue known as the Medici Venus. Plundered from the Palazzo Uffizi by Napoleon in 1802, this celebrated Hellenistic statue was crated up and sent back to Florence in December 1815. Fleet Street, appreciating the coincidence, went for the bottom line, capturing the Platonic assertion that there are two Venuses in western culture, one celestial, the other vulgar:

The Venus of Medicis scarcely has flown,

When Paris, alas! Your next Venus is gone;

And no end to your losses you find:

Well may you in sackcloth and ashes deplore;

For the former fair form had no equal before,

And the latter no equal behind.

Source: http://arlindo-correia.com/venus.html

****************************************

Gwiz, likewise, do we know about Ota Benga, and beyond that, do we know about the likes of Frank Wilderson, Amos Wilson and Tommy Curry, past and present thinkers who provide much needed context which often facilitates a better and deeper appreciation of these historical events

LikeLike